Confidence

hiding among

trees whose families rooted

long before a road

cut into a mountainside

what secrets do they know

whose histories do they hold

who named the town

nestled under ancient boughs

white letters

on a green rectangle

Confidence

is the act of naming

a wish

a reminder

of what brought settlers here

or is it why they persist

how they endure

the isolation

the frigid winters

the parched months

when fire licks at their dreamsSanta Cruz (Holy Cross)

(Note: all the underlined words in this post are links to sources if you would like to explore a topic or a term in greater detail.)

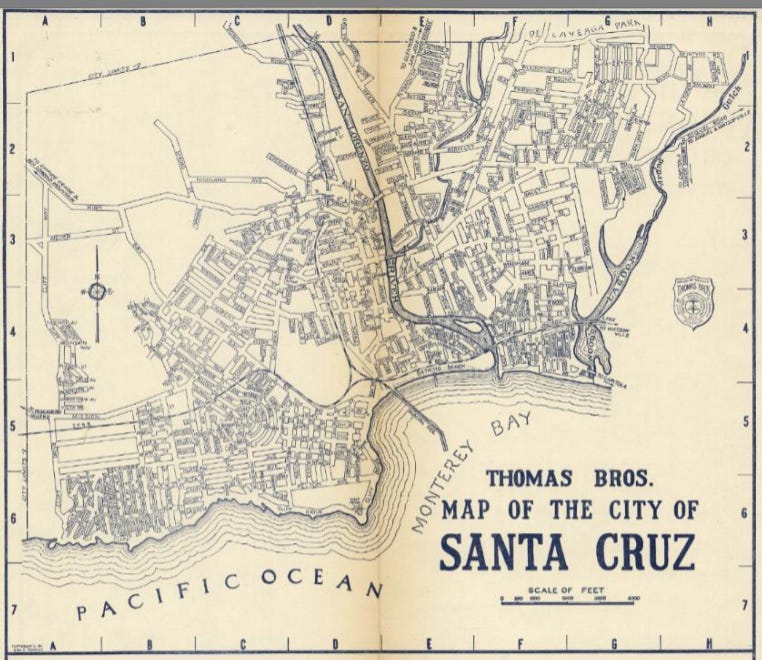

My hometown—the place I have lived for the last thirty years—was named by Spanish missionaries. It is a beachside resort, a hippie hamlet, a quirky college town. It is also one of the most expensive places to live nationwide, and beneath the anything-goes, liberal veneer lies a pernicious I-was-here-first-ism rooted false logic, settler colonialism and white supremacy culture.

On the surface, these isms—these ills—seem to cause me no personal harm. I can bob on gentle waves, turning away from what lurks beneath, never stopping to wonder about the history of the place I call home, the lies that have become truths, the absence of facts, the absence of faces that aren’t white. (To learn more about Santa Cruz history, click this link).

Columbus is the town I called home during adolescence—Nebraska, not Ohio. There’s a history there, too. A history that extends below the paved streets on the parade route I once walked carrying a flute, then wearing a cheerleading skirt, on October days commemorating the man who “discovered America,” but never set foot in Nebraska. A history that flows from the city’s wide rivers. The Loup and The Platte. They both run south of town, near a park named Pawnee to steer the narrative in the direction the namers wanted it to go.

Naming is a curious practice—a conscious choice of what to put in and what to leave out. Mountains, for instance, how are they named?

Hermit’s Peak, near my birthplace in New Mexico, was named in 1867 after a reclusive Italian monk took up residence there. Before that it was called El Cerro del Tecolote (Spanish for Owl’s Peak), but what about the centuries prior to Spanish settlement of the region in the late 1500s? A cursory internet search yields no results for indigenous names for the mountain. Another erasure.

A different peak near my current home carries the name of a man who arrived millennia after its original inhabitants. In 1846, John C. Fremont raised a U.S. flag at its apex, replacing the name it was given during the Spanish Mission period, Gavilan Peak, with his own. (Note: Gavilan, sometimes spelled gabilan, means hawk).

But what was Fremont Peak called before European contact? Does claiming ownership of the land give you the right to name it?

The Amah Mutsun Tribal Band is working to restore the sacred mountain’s indigenous name, Tooyotak, which means the place of the bumble bee in the Mutsun language. (To read Tribal Chair Valentin Lopez’s remarks on the proposed renaming, click this link).

All this musing on naming has not led me to tidy conclusions, but to more questions. Who gets to name a place? How do we decide when to change it? Do the words we attach to places reflect our world view, our values, our state of mind?

Are they passing fancies, or do they cling—seeping into the water we drink, sneaking into our psyches?

Invitation

"What's in a name?

That which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet."

—William Shakespeare

Do you agree or disagree with Shakespeare? Would that which we call a town or a mountain by any other name smell as sweet?

Does this post spark curiosity about the names of the places you’ve lived?

I believe in sharing financial abundance. 100% of subscription payments will be donated to non-profit organizations. In June, donations will go to CHIRLA. For a complete list of the organization Bare supports and to join the conversation, visit Bare’s Community page.

You bring up such important and interesting questions. Could we waltz up to someone else's car, point at it, give it the name, "Mine!" and expect it to truly become our possession? Of course not. Yet not long ago, a certain someone thought he was entitled to do exactly that to an entire gulf. The entitlement is shocking. Thank you for raising awareness on how important it is to be respectful of others, to be considerate, to be logical and inclusive.

I do agree with Shakespeare about a name. Love the smell of roses, regardless of their name. Unfortunately, many of the names that exist today, at least in America, originated from the men who claimed rights to the area. Just because one thrusts a pole into the ground that has a piece of cloth waving at the end, should not give them the right to consider the area theirs. Women do not tend to be so presumptive. Here in Colorado, our current Governor (Dem) refused to honor the native names that were recommended by the native people. 'The names are just too hard for the average person to pronounce,' was Gov. Polis's reasoning. Well, too bad. It's time we, as (new) Americans, learned to expand our tongues to incorporate words and names that may be uncomfortable for us. I'm sure losing one's native homeland was hard for the first people here as well. Enjoy Santa Cruz- my family's former summer homes were located in that breathtaking area!